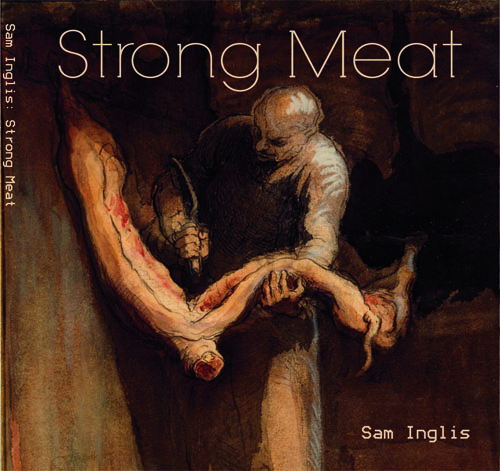

In a spirit of well-meaning folly, I have created an album of traditional songs that have never before been recorded. After all, it's not like the world needs more versions of Pleasant And Delightful. Strong Meat is available now at gigs or by emailing me. It comes with reasonably comprehensive notes on the songs, which you can read by clicking this link.

During the ludicrously long time it took me to put the album together, I also recorded quite a few other folk songs under the mistaken apprehension that they too were unique. Then I found out that someone else had recorded them, so had to leave them off. So rather than offer you tracks from the album on this site, here are the near misses, along with some alternative versions of well-known songs:

The Truth Sent From Above

Also known as The Shropshire Carol, this comes from one of my favourite songbooks, Cecil Sharp's English Folk-Carols. Sharp's tune is not often sung, but Ralph Vaughan Williams collected a very different version in 5/4 and made a choral arrangement which has been quite popular. Which is annoying, because I really wanted to include this on my album.

The Truth Sent From Above

Young Allan

This song is Child ballad number 245. I had never come across a recording of it, but it turns out there is a version on a June Tabor live album somewhere! Who knew that you could bribe your bonny ship to ride out a storm?

Young Allan

Fair Annie

The story behind this very affecting ballad can be traced back at least to the 12th Century. There are quite a few texts known from Scotland, most of them very beautiful but too long to sing, and not associated with tunes. This unusual and poignant American tune is given in Bertrand Bronson's Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads.

(Interestingly, in this and most of the later versions, Lord Thomas is simply a nasty piece of work who treats poor Annie very badly; but in some of the earlier versions, it turns out that the real villains are Annie's family, who have cheated him out of his dowry, and that he's simply using her sister as a means of getting what is rightfully his.)

Fair Annie

The Earl Of Errol

(A new version!) There are lots of texts of this ballad, and several tunes, but none of the tunes was collected with a full text, so I've abridged the words from a couple of different versions. The legal case that is the subject of this ballad was a real one, but the records have been lost. I hope it really happened like this.

The Earl of Errol

Canadee-I-O

There probably isn't a folk fan on the planet who hasn't heard Nic Jones' version of this, which is of course a marvellous thing. Not having heard many other versions, I was intrigued to find the same song on an album by Tish Stubbs and Sam Richards, sounding quite different even though both must have originated with Harry Upton. My version is closer to Tish and Sam's, because, well, you're onto a loser if you try to match Nic.

Canadee-I-O

The Golden Vanity

This unusual Cambridgeshire version of The Golden Vanity -- actually the Valiantry in this case -- comes from the Garners Gay collection by Fred Hamer. This is the first outing for a strange old musical instrument found in my Dad's loft, with a banjo neck and a mandolin body. I brought it back to life but perhaps should have used some more expensive tuners, as it is a pig to keep in tune.

The Golden Vanity

About Me

I used to write my own songs, and still do when there's a dire need. But about five years ago I became very interested in the traditional songs of the British Isles, particularly England and Scotland, and began to work within this tradition. I take particular delight in uncovering obscure songs and less well-known versions of famous ones, and setting them to slightly odd guitar accompaniments.

The big news from me is that I have finally finished my solo album. Strong Meat is a collection of eleven traditional songs from the British Isles, America and Australia, the common thread being that all of them are, as far as I know, previously unrecorded.

In the spirit of wilful obscurity, it's available on CD only, and I have no plans to add it to any streaming sites. You can buy a copy at gigs, or email me and I'll pop one in the post.

For more details, see the Music page.

Strong Meat

by Sam Inglis

a collection of previously unrecorded traditional songs

Ibby Damsel

On his song-collecting expeditions to the Appalachian Mountains, Cecil Sharp discovered both a vast treasure trove of material and a number of singers who impressed him very much. Some of the most memorable songs in his English Folk-Songs From The Southern Appalachians were collected from Rosie Hensley, who always seemed to supply particularly beautiful melodies. Many are now well-known, but this fragment has, as far as I know, never been recorded. Nor is it obviously related to any other song from the English or American traditions, so perhaps it was composed by Rosie herself?

William Guiseman

This murder ballad was first published by George Kinloch as long ago as 1827. Dean Christie printed the same words with a different tune, and I found it in Bertrand Bronson's compendious Traditional Tunes Of The Child Ballads. It is listed there as a variant of the well-known and widely recorded 'William Glen' or 'Captain Glen', and in turn as a derivative of 'Brown Robyn's Confession', but the two actually have little in common. 'William Glen' is not narrated from the murderer's point of view, and it is a supernatural storm that reveals the presence of a killer on board; 'William Guiseman' takes the form of a confession, and it is the ship herself that gives the game away by refusing to sail.

Musically, this song is almost unique in the British folk tradition in being bi-modal: the first half of each verse uses one of the natural minor scales, while the second half employs a major scale.

The Fire Of Frendraught

A text for this Scots ballad was published by William Motherwell in 1827, and Dean Christie supplied this melody forty years later 'from Banffshire tradition'. Despite its dramatic narrative, it has not been revived in recent memory. Though based on a real event which took place in 1630, the song is, by all accounts, a gross libel on the unfortunate Lady Frendraught, who never intended to burn her guests to death.

The Freemason's Hymn

The English folk tradition includes a large number of bizarre religious songs, which I love. This one comes from William Alexander Barrett's interesting but slightly neglected book called simply English Folk-Songs. Barrett cautions the reader: 'It is supposed by the "popular and uninstructed world at large" that this song contains all the secrets of Freemasonry. Those who will believe this statement will believe anything.' It's not clear where Barrett's tune comes from, but it seems likely that he took the text from a written source, since a broadside with identical words is found in the Bodleian Library's collection.

Heaving Of The Lead

This little tune was 'pricked down' by the poet John Clare and printed in George Deacon's classic John Clare And The Folk Tradition. It started life as a composed song, but Clare's melody differs significantly from the original printing, and is presented as a fiddle tune, so he presumably learned it by ear.

I'm A-fading Day By Day

This song was collected from gypsy singer Elizabeth Smith by Reginald Gatty and Ralph Vaughan Williams, but remained in the archives for years; it seems likely that they had trouble transcribing the melody and thus chose not to publish it for fear of getting it wrong. It finally saw the light of day in 2013, in Paul and Liz Davenport's collection Down Yorkshire Lanes. I have followed the tune and words as given there.

The Little Room

Some folk songs are more talked about than sung, and this hallucinatory carol is an example. The tune was noted by Miss K Sorby from the singing of a Mr Samson Bates and a Mr Felton, and published by Cecil Sharp in his English Folk-Carols. There he describes how it is 'very popular in this part of Shropshire where, despite its great length, it is frequently sung at Christmas time by small parties of two or more men', with the words being read from a chap-book called A Good Christmas Box. Sharp prints it in two parts, totalling thirty-four verses; for the sake of brevity I have edited this version from the first part alone.

Coprolite Digging Forever!

It is bending the rules a little bit to consider this a folk song, since I have no evidence that it was ever sung, and no tune is recorded, but I found it too fascinating to leave out. The Victorian and Edwardian folk-song collectors achieved much better hauls in neighbouring Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex than in my own county of Cambridgeshire, and apart from a rare version of 'Lucy Wan', most of the songs that have been collected here are widely known from other areas. Not so this song, which is unique in several respects.

The text comes from a Victorian broadside reproduced in a book by local historian Bernard O'Connor, who has documented the now-vanished coprolite mining industry that flourished from the mid 19th Century til the outbreak of World War 1. It is remarkable for the amount of detail and local colour it contains, identifying individuals and places by name, and for documenting an industry that is now utterly extinct. The tune is my own.

The Downs

Several versions of this shipwreck ballad have been collected on the East Coast of Scotland, and this one comes from the Greig-Duncan collection. It's interesting that it should have flourished there, since it preserves details of an incident that took place hundreds of miles away, on the coast of Ireland. How accurate those details are is impossible to guess, but it is known that a ship called the Middlesex Flora was wrecked at Dundrum in 1825, though she had sailed from Barcelona rather than London. A field recording exists of source singer William Hutchinson singing the song to a different tune, but I'm not aware of any recordings made by revival artists.

Gargal Machree

This poignant and probably fragmentary song was collected by John Meredith from a prolific singer called Sally Sloane, who lived in Australia but learned most of her material from her Irish grandmother. It was published in Meredith and Hugh Anderson's Folk Songs Of Australia, where they note that although the title sounds like a corruption of the Irish 'Grá Geal Mo Chroi', the song itself is completely different.

The White Fisher

Texts for this wonderful Scots ballad have been known and printed since the 19th Century, but it was thought to have passed out of the oral tradition until James Madison Carpenter heard it sung by Bell Robertson in the 1920s. Carpenter never published his collection, and it has only recently become available. The collection includes two recordings of Robertson singing the song, but as far as I know, it has not yet been recorded by any revival artist.